Appropriate Risk Management in the Flying Community

By MAJ STEVE BOSTWICK, AMC FLIGHT SAFETY

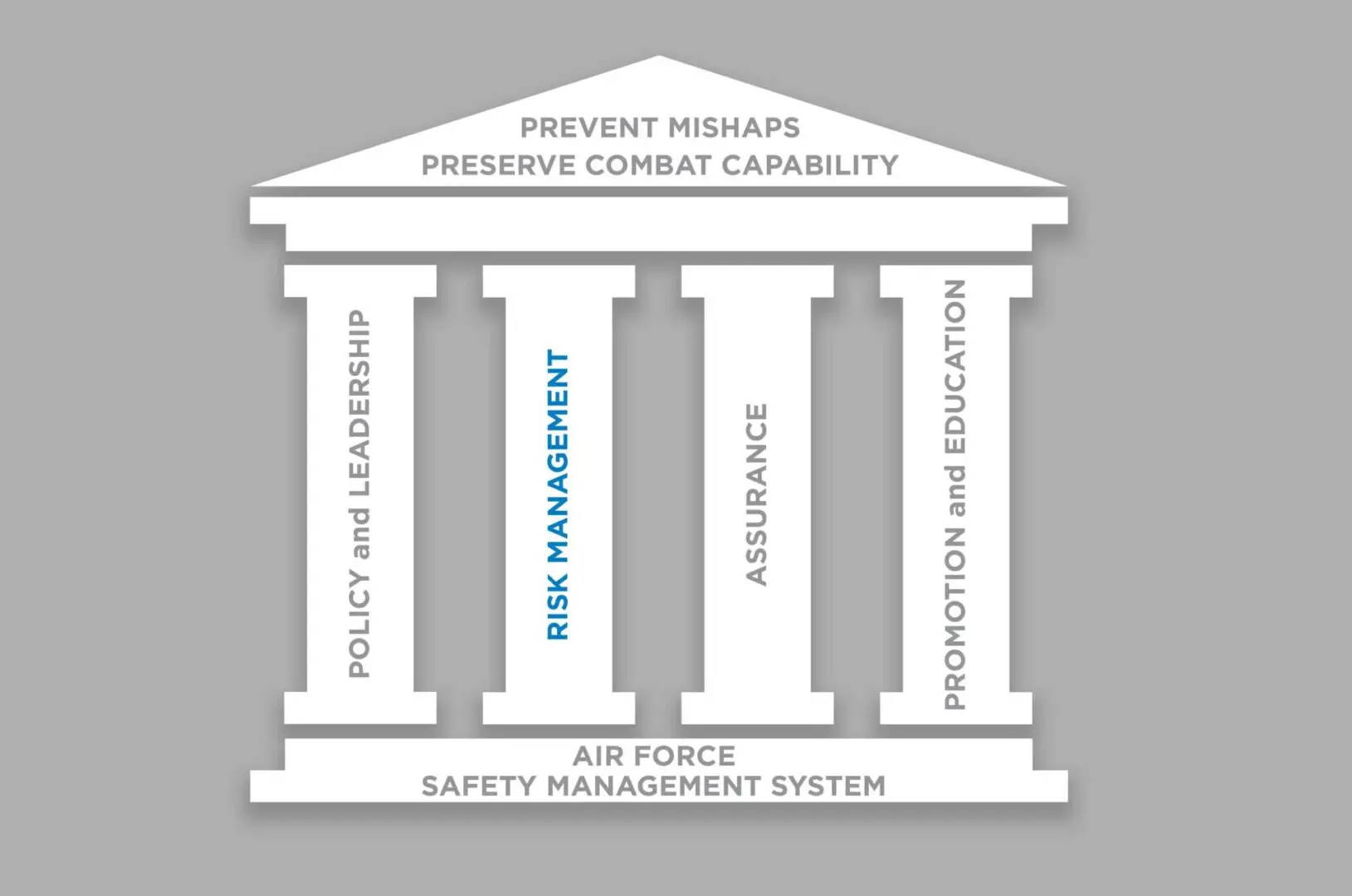

Risk Management (RM) is one of the four pillars found in the Air Force Safety Management System and is the core to Air Force Safety’s sole mission of mishap prevention. The RM process is both deliberate and foundational, and is structured into a five-step process outlined in DAFI 91-202, The US Air Force Mishap Prevention Program: identifying hazards, assessing hazards, developing controls and making decisions, implementing controls, and supervising and evaluating. Within the confines of flight safety, most aircrew recognize this process as Operational Risk Management (ORM). Air Mobility Command aircrews utilize ORM for every mission; however, to appropriately use this important tool, our flyers must ensure that they actively contribute to the assessment of their profiles, provide genuine responses when annotating risk, and understand the fundamental purpose of the ORM program. To ensure appropriate use of ORM, it is imperative that experienced aircrew personnel teach our future generations of flyers about its application. Additionally, it is crucial for leadership to promote and foster an environment that embodies the fundamental values of ORM and encourages Airmen to highlight and mitigate risk.

So there I was—a new KC-135 aircraft commander deployed to Central Command, executing missions for both OPERATION INHERENT RESOLVE and OPERATION ENDURING FREEDOM. On this particular day, my crew and I had been sitting alert, able to respond at any moment to the aircraft in support of either operation. In this particular case, on day two of our alert, we were informed that we needed to fly a normal mission, which required us to report to the squadron within the next four hours. Our method of notification was a physical schedule posted on our trailer, which met all legal requirements regarding crew rest; however, this timing was not within our normal schedule. Unsurprisingly, my crew and I did not get great sleep (duration or quality), and once we arrived at the squadron, we discovered that the assigned mission was scheduled to last more than 10 hours. I annotated everything on the ORM form, asked my crew if they felt comfortable proceeding with the mission, and took the form to the Operations Officer (DO). Our overall ORM score required Operations Group Commander approval, and the DO was not thrilled by this news.

I was asked numerous questions with an aggressive tone:

“Why didn’t you get better rest?â€

“You were sitting alert, did you not know you could be called in?â€

“You realize that I will have to wake up the Group Commander, right?â€

Although, in my mind, I had reasonable rebuttals to each question, I simply replied, “yes, sir.†The next question from the DO made me realize something was amiss, when he asked, “Well, if we take a look at the (scheduling) board and find a shorter sortie, would you be willing to fly?â€

I was astounded. Willing to fly? I realized my Operations Officer assumed my crew was attempting to use ORM as a method to avoid flying. I replied, “Sir, we are willing to fly now. I just need the appropriate level of approval (risk acceptance).†This moment was the first in my career that I realized that there were misconceptions or perceived misuses of ORM.

Later in my career, when I was an instructor in Undergraduate Pilot Training, I saw that many students and younger instructors possessed similar misperceptions about why we conduct ORM. DAFI 91-204, Safety Investigations and Reports, explains that “risk management is an expected function for all organizations … there is a responsibility to assess the associated risks, evaluate risk mitigation options, implement risk management measures, evaluate the residual risks, document approval at the appropriate level…†This excerpt explains exactly how we use ORM before aviation sorties.

To simplify, units and aircrew identify the hazards associated on a particular mission, quantify the level of risk, explore methods to eliminate or mitigate risk, and accept the residual risk at the appropriate level. The Risk Acceptance Authority is the previously mentioned “appropriate level,†which can be the aircraft commander or perhaps unit leadership at higher levels. Regardless, the Risk Acceptance Authority may choose to accept or not accept the outlined risk.

If an aircrew requires approval at a higher level of authority, and they seek said approval, it should be understood that they are effectively willing to fly the mission. Never should a crew “pass the buck†to leadership with the intent that the higher commander will cancel the mission on the aircrew’s behalf. If a crew determines that the accomplishment of the mission is not justifiable due to the associated risk, then the responsibility falls to them to call “knock it off.â€

Once the risk is accepted and the mission is in execution, aircrews are responsible for continuing risk management, as it is a varying process. On a multileg mission, flyers are expected to reevaluate their ORM. Aside from checking updated weather and Notices to Air Missions, it is sometimes overlooked. Additionally, successful ORM requires honest input; intentionally omitting or reducing the risk level to ensure a lower level of risk acceptance does not benefit the Air Force or the aircrew. How do we as an organization remedy these quandaries?

To institute sound ORM, flying units must rely on good educational practices and supportive leadership to promote the tenets of risk analysis and mitigation. When a crew sits down at the briefing table, they must work together to identify the hazards and the inherent risks associated with those hazards. Once the risks have been identified, each crew member must determine if there are safe and legal measures to eliminate or mitigate the risk. Any remaining, or residual, risk must be accepted at the appropriate level, but only if the aircrew is willing to also accept this risk. Flying is an inherently dangerous business, and we are expected to accept some risk in the defense of our nation. We cannot accept unnecessary risk, which is risk that could have been alleviated, especially when it may lead to a mishap. Comprehensive risk management does not necessarily eliminate risk; rather, it empowers our members to identify hazards while making sound and robust decisions that ultimately lead to mission success.